21 May Integrating Dental Care into Alzheimer’s Management: A Call for Proactive Intervention

At House Call Dentists (HCD), we have dedicated ourselves to a mission born from compassion and necessity by delivering comprehensive in-home dental care to seniors, the homebound, and individuals grappling with complex medical conditions. Our specialization places us at the forefront of understanding the intricate relationship between overall health and oral health, particularly for vulnerable populations like those living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The struggles that these individuals and their caregivers face are unique and profound. They demand a specialized, empathetic, and proactive approach to dental wellness.

Recognized Leaders in Dental Care for Patients with Alzheimer’s

Recently, House Call Dentists was honored to be included in the Alzheimer’s Association Ask the Expert series, presenting vital information on dental care to dementia caregivers at both their West Coast and East Coast Chapters. This invitation, extended for the purpose of educating family members and caregivers, underscores the trust and long-standing relationship that HCD has cultivated with the Alzheimer’s Association. It highlights a shared commitment to supporting this community and recognizes HCD’s position as a thought leader in providing essential dental services and education to this constituency. In this article, we seek to expand on the critical insights shared during those presentations while issuing a call to action for families, caregivers, and the wider dental community.

The Alzheimer’s Challenge: Why Oral Health Suffers

Alzheimer’s disease progressively impacts cognitive function and physical abilities, creating significant hurdles for maintaining oral hygiene. What might seem like simple daily tasks – such as brushing, flossing, or even recognizing discomfort – become increasingly difficult obstacles.

- Cognitive Decline: Memory loss and confusion can lead individuals to forget how to brush their teeth, or recall if they have done so. They may not understand the purpose of oral care or recognize dental tools. Research has demonstrated a correlation between cognitive impairment and tooth loss (Xiang et al., 2021).

- Decreased Motor Function: Physical coordination diminishes as the disease progresses, making the mechanics of brushing and flossing challenging or impossible for the individual to perform independently.

- Sensory Changes: Altered taste perception or discomfort in the mouth might go unreported or be difficult for the person to articulate.

- Behavioral Changes: Resistance to care is common, stemming from fear, confusion, misunderstanding, a feeling of lost autonomy, or discomfort. A person might refuse to open their mouth, become agitated, or clamp down.

- Medication Side Effects: A primary challenge is dry mouth (xerostomia), a common side effect of hundreds of medications frequently prescribed to older adults and those with chronic conditions, which include antidepressants, antihistamines, diuretics, and pain relievers. Saliva is the mouth’s natural defense mechanism. It neutralizes acids and washes away food particles. Without adequate saliva, the risk of cavities, gum disease, and infections will skyrocket. It’s estimated that a staggering 89% of geriatric patients experience dry mouth (Elangovan, 2022)..

- Bruxism: Involuntary grinding or clenching of teeth (bruxism) can occur, sometimes associated with specific types of dementia like frontotemporal dementia (affecting up to 30% of these patients). This can lead to jaw soreness, difficulty opening or closing the mouth, and excessive wear or fracturing of teeth. Traditional nightguards may pose safety risks for individuals with cognitive impairment, necessitating careful evaluation by a specialized dental team.

The Peril of Delayed Dental Intervention for Patients with Alzheimer’s

Dr. David Blende, our founder, often speaks of a critical yet frequently overlooked window of opportunity to maintain oral health after the initial diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. “I think I’m alone in the forest,” he notes, “when I tell patients and dentists that at the first moment you get a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s for a family member, you need to challenge the family dentist to think ahead and say, ‘If you do not take care of my afflicted family member that has Alzheimer’s dental needs now while they’re still compliant and cooperative, you will not be able to do so in six or seven years when they become combative and have stopped brushing their teeth.’”

This isn’t just advice; it’s a clarion call for dentists to be proactive. Standard dental practices are rooted in reaction and response – fixing problems only when they arise. However, the progressive nature of Alzheimer’s demands foresight and a preemptive approach to oral care. Interesting, the dental community readily embraces proactive measures in other contexts. The American Dental Association’s (ADA) protocols, for example, direct dentists to address oral health issues before a patient begins chemotherapy or undergoes radiation treatments for head and neck cancer. So although the ADA acknowledges the heightened risks that these treatments pose to oral tissues, this guidance does not extend to Alzheimer’s and related conditions.

As Dr. Blende points out, “I’ve never seen an article warning dentists to inform the family of what lies ahead of them when a patient with Alzheimer’s loses the inclination to brush or care for their teeth.”

This gap in preventative guidance is alarming. Families are often left unprepared for the inevitable decline in the self-care abilities of their loved ones. By the time severe dental problems manifest, the patient may be in the later stages of dementia, making treatment substantially more complex. The result is undue stress for both the patient and caregiver, along with dental treatments that will likely be exponentially more costly.

“The people that traditional dentists have never treated are the ones who are referred to us,” Dr. Blende explains. “By that time, it’s too late. The treatment is very involved and usually very costly.” As with all aspects of oral health, prevention is key. Early intervention, establishing a baseline of good oral hygiene, and planning for future needs while the patient can still cooperate is essential preventive care.

The Alzheimer’s Domino Effect: Common Oral Diseases and Systemic Links

Neglecting oral health in Alzheimer’s patients doesn’t just lead to mouth problems; it can severely impact their overall health and quality of life. While many people associate oral health with appearance, cosmetics should be the least of their concerns. Oral health is intrinsically linked to total body health.

Dental Decay (Cavities)

Caused by plaque bacteria that feeds on carbohydrates left on teeth, which erodes the enamel. Symptoms include visible black or brown spots, holes, and temperature sensitivity. Dry mouth accelerates this process. Acidic drinks also wear away enamel. A healthy mouth pH is around 7.5 or higher. Sodas, sports drinks, and some juices are highly acidic. They lower the pH level in the mouth. Studies show that enamel begins to soften (or demineralize) at a pH just below 5.5. Sodas, for instance, are much lower than that. Tap water is generally the best beverage choice for dental health.

Gingivitis

The initial stage of gum disease, characterized by inflammation, redness, and bleeding gums caused by plaque buildup. It’s reversible with good hygiene and professional cleanings.

Periodontal Disease

If gingivitis is left untreated, it progresses to periodontal disease. This involves the destruction of the bone supporting the teeth. Gums recede to expose roots, plaque and calculus accumulate, and teeth become loose. This leads to difficulty chewing, pain, and eventually tooth loss. The phrase “long in the tooth,” a colloquial expression used to describe old age, actually originates from the gum recession seen in severe periodontal disease. Loose teeth also pose a serious aspiration risk, especially in individuals who have difficulty swallowing.

Dental Abscess

A severe infection, often resulting from untreated decay or gum disease, forms a pocket of pus. It can cause localized swelling, intense pain, fever, and malaise. More critically, dental infections can spread rapidly through facial tissues, potentially causing airway obstruction, systemic infection (sepsis), and even death. Tragic headlines have documented cases where neglected dental abscesses in care facilities led to fatal outcomes and significant fines.

Systemic Health Implications

The mouth is a gateway to the rest of the body. Bacteria from oral infections can enter the bloodstream, contributing to serious systemic diseases:

- Pneumonia: Aspiration of oral bacteria is a major cause of pneumonia, especially in frail elders.

- Heart Disease: Chronic inflammation from gum disease is linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular problems.

- Stroke: Oral bacteria have been implicated in stroke risk.

- Diabetes: Gum disease can make blood sugar control more difficult, and diabetes, in turn, increases susceptibility to gum disease. The co-occurrence of diabetes and dementia can even have an additive negative effect on cognitive impairment.

- Cognitive Impairment: Emerging research shows a strong association between tooth loss and cognitive decline. Studies suggest individuals with more tooth loss have a significantly higher risk (up to 48%) of developing cognitive impairment and dementia (up to 28%).

Poor oral health diminishes quality of life through moderate to severe pain, malnutrition due to difficulty eating, altered communication, social isolation (reduced smiling), and the need for emergency dental care. Conversely, good oral health supports a positive self-image, comfort, the ability to eat nutritious foods, clear speech, and better general health.

Practical Strategies for Caregivers: Supporting Oral Health at Home

Caregivers are the front line in maintaining the oral health of individuals with Alzheimer’s. Despite the challenges, maintaining consistent and gentle care can make a profound difference.

Daily Hygiene Routine for Alzheimer’s Patients

Brushing

Aim for twice daily for two minutes each time. Use a soft-bristled brush (manual or electric) and a pea-sized amount of fluoridated toothpaste. Brush gently in a circular pattern, angling towards the gums, and don’t forget to brush the tongue.

Flossing

Once daily is recommended. Floss holders or picks might be easier than traditional floss. Waterpiks or interdental (proxy) brushes can also be effective alternatives, especially for cleaning around bridges or implants.

Mouthwash

Use an alcohol-free mouthwash. Choose one formulated for gum health (anti-gingivitis) or with fluoride for cavity prevention, depending on needs. If the person cannot rinse and spit, wipe mouthwash onto teeth using a toothbrush or sponge swab, ensuring all surfaces are covered. Check cheeks and vestibules (space between cheek/lip and gums) for trapped food.

Managing Swallowing/Spitting Concerns

Perform oral care with the person sitting upright, head tilted slightly forward. Work over a sink (placing a brightly colored washcloth at the bottom can help locate dropped items) or use an emesis basin. Use minimal liquid.

Denture Care for Alzheimer’s Patients

Dentures must be removed nightly for cleaning and to allow tissues to rest. Clean debris off the denture and inside the mouth. Soak the denture overnight in water or a denture cleaning solution (never hot water, which can warp them). Store in a labeled case when not worn. If adhesive is used, ensure all remnants are removed from both the mouth and the denture daily.

Addressing Dry Mouth

Encourage sipping still water throughout the day. Use over-the-counter saliva substitutes (like Biotene sprays or gels). Sugar-free xylitol-containing mints or gum can help stimulate saliva flow.

Overcoming Resistance to Care with Alzheimer’s

When caregivers are faced with refusals from patients with Alzheimer’s, they should try to understand the underlying cause.

Self-Esteem

The person may feel babied, bossed, or embarrassed. Hand them the toothbrush and invite them to brush themselves first. Offer choices (e.g., toothpaste flavor). Explain why mouth care is important (e.g., “This helps keep your mouth comfortable so you can enjoy your meals”). Use demonstration (“watch me brush”) and positive reinforcement. Aim for autonomy and partnership.

Self-Conscious

They might feel vulnerable or disconnected from the caregiver. Ensure privacy and a calm environment. Build rapport and trust. Find common ground or shared positive memories related to oral care routines. Offer genuine words of encouragement.

Well-Being

Fear of pain, discomfort, or misunderstanding the process can cause resistance. Always gain permission before starting. Slow down, explain each step simply. Take breaks as needed. Allow ample time for response (up to 30 seconds). Show them the toothbrush, let them touch it. Offer a comforting object, provide reassurance, or gentle touch (like rubbing a shoulder). Establish a consistent routine – same time, same place each day.

Physical

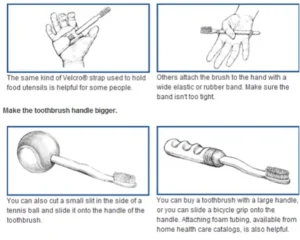

Underlying dental issues, discomfort, or sensory preferences could be the problem. Consider different toothbrush types (color, texture, electric vs. manual), toothpaste flavors, water temperatures, or even changing the location or time of day for brushing. Playing calming music might help. If resistance persists or there are signs of pain, a dental evaluation is crucial.

For persistent challenges, adaptive tools like cheek retractors or specialized mouth props can sometimes aid access, but should ideally be used under guidance from dental professionals.

When to Call the Dentist: Recognizing the Signs

Be vigilant for signs that professional dental attention is needed:

- Persistent bad breath

- Bleeding gums

- Refusal to eat, pain or difficulty while chewing

- Unintended weight loss

- Sore spots in the mouth or under dentures

- Redness under dentures

- Loose teeth

- Poorly fitting dentures

- Changes in behavior related to the mouth (e.g., resistance to touch)

- If it has been over a year since the last dental visit

House Call Dentists: Bringing Specialized Care Home

Recognizing the immense difficulty many families face in getting loved ones with dementia to a traditional dental office, House Call Dentists bridges the gap. We bring the dental office to you, equipped with portable technology to provide comprehensive care in the comfort and familiarity of home. Our services include:

- Dental Examinations & Diagnostics: Comprehensive assessments, digital X-rays, intraoral photos, periodontal evaluations, and oral cancer screenings.

- Preventative Care: Professional dental cleanings.

- Restorative Care: Fillings, crowns, bridges, extractions, and fabrication/adjustment of dentures and partial dentures.

We tailor our approach based on the individual’s needs and stage of dementia,

- Restorative Care: Aimed at repairing teeth, restoring function and esthetics, eliminating pain, and improving quality of life.

- Palliative Care: Focused primarily on eliminating pain and discomfort, managing issues like dry mouth, addressing urgent problems (cavities, broken teeth), supporting oral hygiene efforts, providing psychological support, and ultimately improving quality of life when extensive restorative work may not be feasible or desired.

Our team, including specialists like Dr. Nitika Gupta and Dr. Lindzy Goodman, has specific training and experience in working with vulnerable populations and managing the complexities of geriatric and special care dentistry. We understand the importance of patience, communication, and adapting techniques for individuals with cognitive impairment. HCD also provides education and presentations for caregivers, family members, and healthcare professionals, reinforcing our role as a leading resource. Our team is available 24/7/365 for dental emergencies.

Some patients simply cannot tolerate dentistry and may require sedation. We are experienced and trained in hospital settings, which has allowed us to treat a diverse range of patients with complex needs over the past 40 years. For those who need to be asleep, we offer sedation dentistry options in our offices and at the hospital. We provide oral medications, inhalation agents, I.V. sedation, and general anesthesia for those with mild to severe anxiety, or those who cannot physically, medically, or cognitively tolerate dentistry. We often offer a combination of these methods for the safest and most predictable outcome of care.

The Path Forward: Embracing Proactive Partnership

Alzheimer’s is challenging, and oral health is a critical component of overall well-being that cannot be ignored. The request from the Alzheimer’s Association for HCD to present to both East and West coast chapters is a reflection of the growing recognition of this need and the trust placed in specialized providers like HCD. We are committed to being thought leaders in this space, advocating for better care standards and providing practical solutions.

Proactive dental care, initiated early after an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, is paramount. Families must be empowered to advocate for this foresight with their dentists. Waiting until problems become severe is a disservice to the patient, leading to preventable pain, systemic health risks, and costly, complex interventions later.

We understand the complexities and the overwhelming responsibilities that caregivers must shoulder. You are not alone. We work together with families, caregivers, and traditional dentists to ensure that every individual living with Alzheimer’s can maintain the dignity, comfort, and health that comes with a healthy smile.

If you are caring for someone with Alzheimer’s or other complex needs, or if you are a healthcare professional seeking resources, please reach out to House Call Dentists.

References

Elangovan S. (2022). TASTE DISORDERS AND XEROSTOMIA ARE HIGHLY PREVALENT IN PATIENTS WITH COVID-19. The journal of evidence-based dental practice, 22(1), 101687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebdp.2021.101687

Qi, X., Zhu, Z., Plassman, B. L., & Wu, B. (2021). Dose-Response Meta-Analysis on Tooth Loss With the Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(10), 2039–2045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.009